Why should you be excited that a historic whaleship sailed into a marine sanctuary and saw whales?

It is a valid question, and one I have asked myself as I became increasingly excited and passionate about the trip. On July 10th I boarded the Charles W. Morgan, the last wooden whaleship in the world, as a part of the 38th Voyagers program with Mystic Seaport, funded partially by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. On July 11th we sailed into the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary on a mission of peace to the first whales seen off the deck of the Morgan in nearly 100 years. It is an event largely without precedence in our country's relationship to its troubled history with the environment. To use history as the literal vehicle for scientific education about the future is something to be excited about.

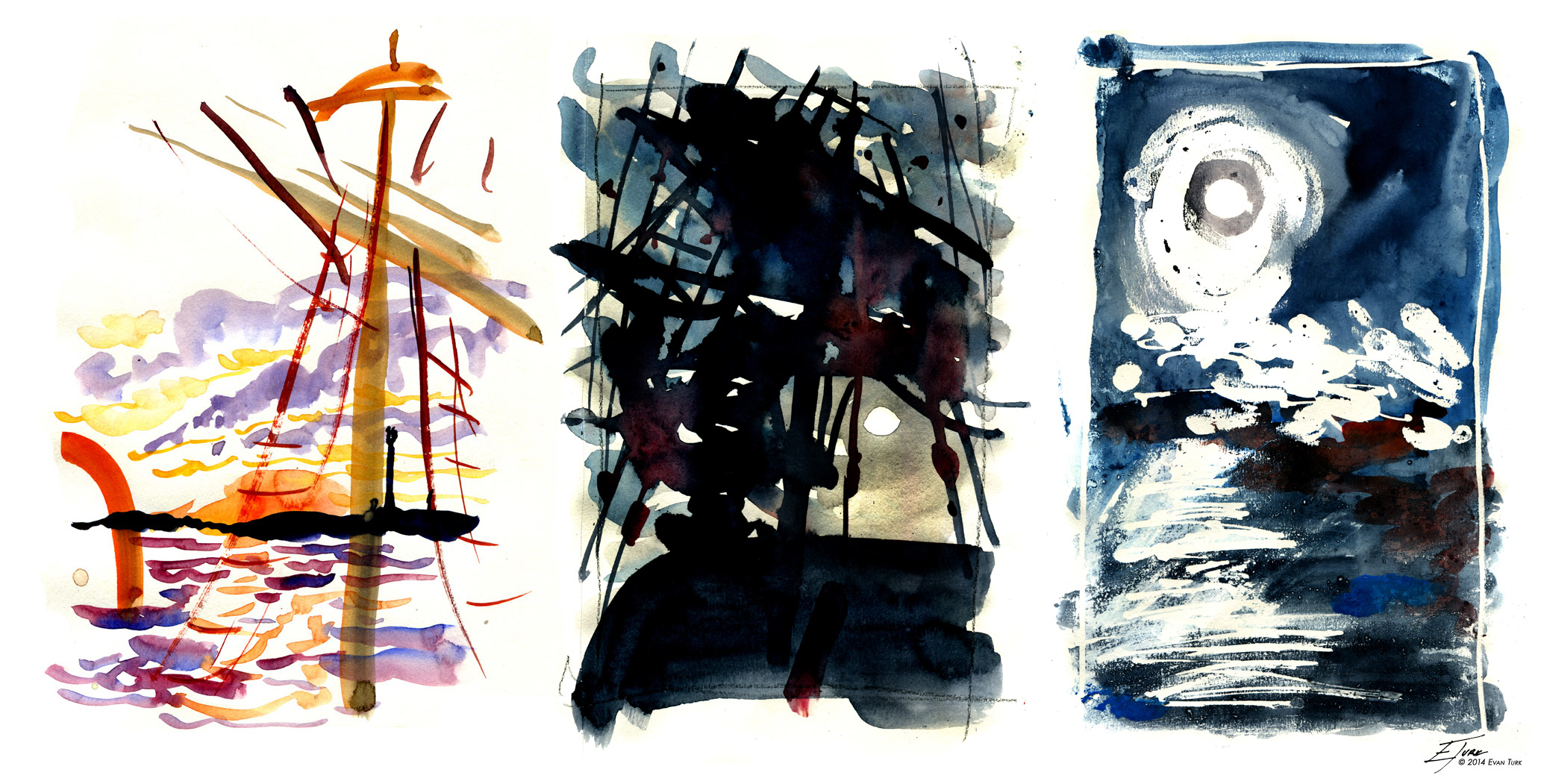

|

| Sunset, moonrise, and glittering moonlight over the decks of the Morgan |

We approached the Morgan, moored out past the harbor in Provincetown, in the glow of a radiant sunset. As we climbed aboard and began our orientation, I kept rubbernecking to the sunset behind us. After the orientation we had plenty of time to sit on deck, talk amongst the voyagers, and watch the nearly full moon glitter across the water through the rigging.

|

| Captain Kip Files |

The next morning, after breakfast, we awoke and began preparing for our sail. Captain Kip Files introduced us to the voyage as we prepared to hoist the anchor and head out towards Stellwagen.

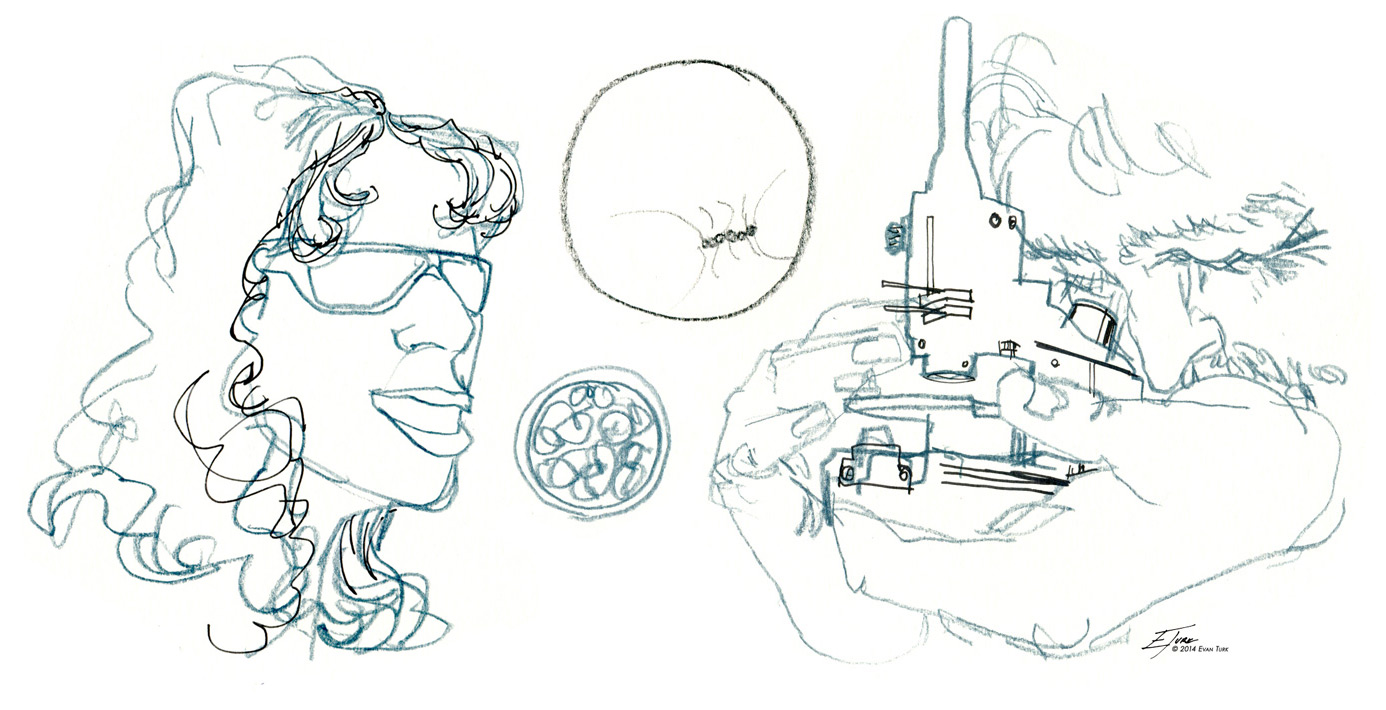

|

| Chief Mate Sam Sikkema, Second Mate Sean Bercaw, and Third Mate Rocky Hadler |

Chief Mate Sam Sikkema, Second Mate Sean Bercaw, and Third Mate Rocky Hadler (whose birthday it was!) kept the ship and crew moving smoothly as the 38th voyagers wandered about, oohing and ahhing over the experience of being on board.

It took the combined teamwork of most of the crew and guests to haul the 1600 pounds of anchor aboard. With the ship liberated from her root, the tugboat pulled us out to sea.

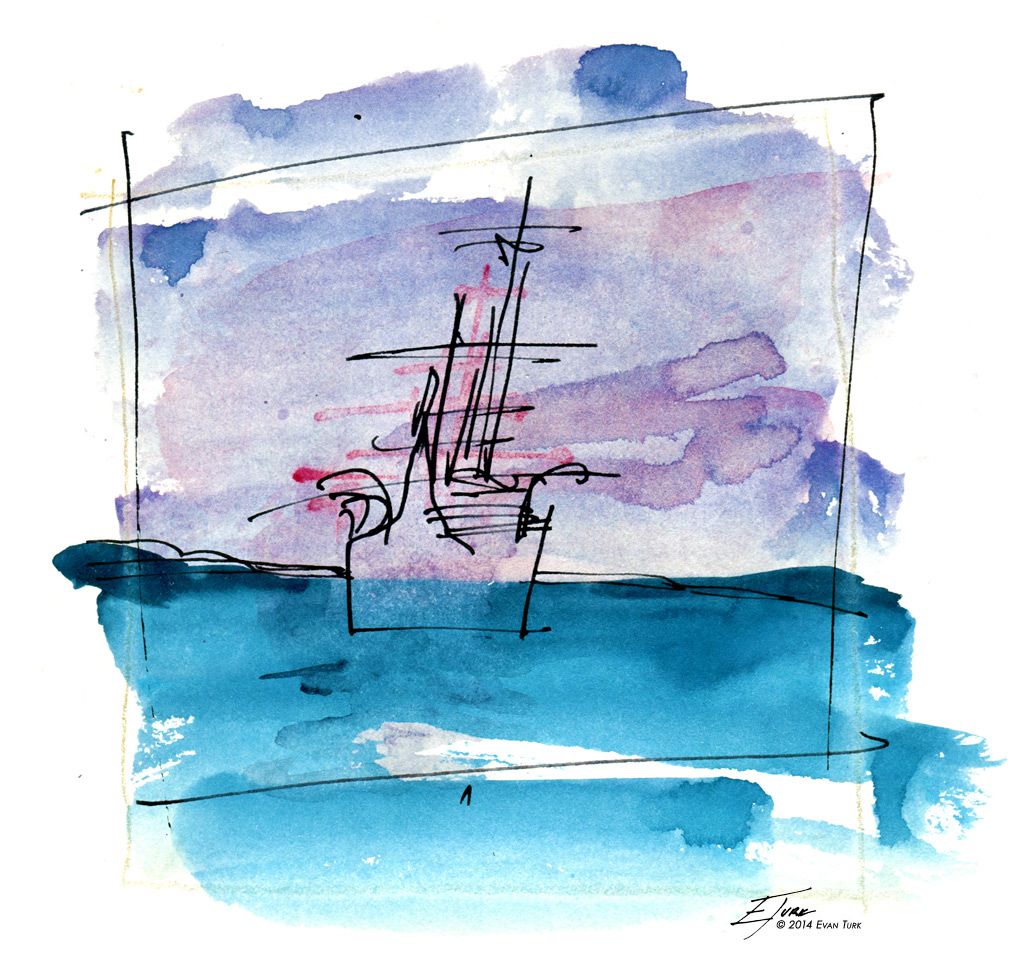

The tiny figures of the deckhands were suspended 10 stories above us as they climbed aloft and began to release the sails.

As the sails began to descend, the entire landscape of the ship would change from one minute to the next. The sails became like canyons across the deck, funneling the wind up and propelling the ship forward on her own power.

As they unfurled the mainsail, it billowed down like a heavy stage curtain until it filled with wind and held taut.

In full sail, the masts soared over the deck like immense, luminous towers that the crew would rotate to follow and catch the wind. The ship moved forward towards the Sanctuary, with its crew of artists, educators, and researchers.

|

| Anne DiMonti and Gary Wikfors |

Myself and the other 38th voyagers scurried about, working on our various projects. The scientists began their observations and measurements. Anne DiMonti of the Audobon Society and Gary Wikfors, marine biologist and musician, were two that assisted in dropping a phytoplankton net over the side to examine the types of microscopic life that were living in the bay. On a voyage into a whale sanctuary, it's amazing to see the other side of the size spectrum of life in the same sea.

|

| Beth Shultz |

Beth Shultz, a literary scholar, professor, and collector of the art of Moby Dick, was on board absorbing the sights, sounds, and smells of a whaleship and creating poetry from the experience. Other voyagers used photography, video, and historic navigational tools to record their fleeting time aboard.

Then came the moment we had all been waiting for. With the tugboat gone, we were at full sail and entering the Marine Sanctuary. Suddenly, from up in the masts, the shout came out: "WHALE!"

And there, just over the starboard side of the ship, a minke whale's arched back crested the water and slithered back underneath. This was the first whale seen from the deck of the Morgan in almost 100 years. We watched her fade into the distance as we sailed by, her glistening fin surfacing every so often until she disappeared under the water.

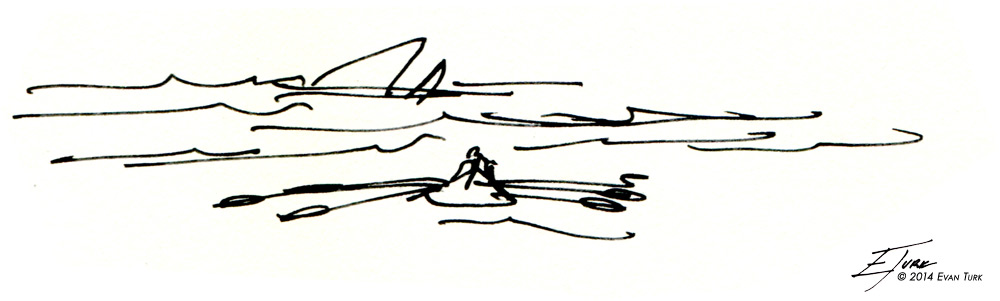

As we sailed deeper into the sanctuary, the whaleboat was lowered over the side, in the same way it would have been during a whale chase.

In the distance, we began to see spouts, the shimmering exhalation of the whales.

Soon we were surrounded by humpback whales, surfacing, feeding, and spouting. The tiny whaleboat gingerly approached them, becoming dwarfed by the massive creatures.

With no malice on either side, the crew on the whaleboat watched as humpback whales surfaced, fluked, and fed just a little ways from their boat. How magical to be in the same place as a whaler from the Morgan, but with no task to do, no prey to kill, just time to sit and watch in awe.

The whales came closer to the Morgan, raising their elegant tails into the air and mightily slapping the surface of the water right next to the ship. It's hard not to think that the whales are aware that they are communicating with us. Whether or not they were trying to directly say something, their actions communicated with us nonetheless. They were not fleeing, they were not attacking, we were merely two species sharing the same speck of ocean for a time.

The crew and guests, meanwhile, buzzed about in a state of euphoria. Nearby, prominent marine biologist and explorer Sylvia Earle was interviewed about her thoughts on the Morgan's voyage into the Sanctuary. She spoke about how until recently, and in the time of the Morgan's whalers, it was always taken for granted that there would always be enough fish, enough whales, enough ocean. It is only a new change in perception that we realize that, small though we may be, we have an enormous impact on our environment and it cannot be taken for granted that it will always be there. This new awareness fills the sails of this 38th voyage and propels the Morgan forward on her new journey.

|

| Gary Wikfors plays a German waldzither built during the same time period as the Morgan as we were towed back into port. |

The Charles W. Morgan is an amazing confluence of what is important about history, and what is important about the future. Her history knits together the entire world, through her journeys and through the men who sailed aboard her. The cargo she brought back, spermaceti, oil, and baleen, served as the predecessors of the plastics industry and the industrial revolution. The light created from the oil and wax of sperm whales lit the world of the 19th century. The bodies of whales fed hungry people across the world after World War II as mechanized factory whaling took hold and decimated whale populations.

Today, our oceans are in an even more deplorable state as we harvest

them beyond their breaking point and pollute them beyond all reason. But

as perceptions of the natural world change, whales

offer a symbolic embodiment of this change. These immense creatures that

were once

floating commodities, are now seen as one of the greatest ambassadors of the

awe of the natural world.

The sailing of this ship is not just an event that is

important to New England and its community that is so inextricably linked to whaling

history, it is of nationwide and worldwide importance. To be able to

resussitate a piece of history and use it as a catalyst for education and

change is an amazing feat, and one that can act as an inspiration going

forward. History and tradition do not need to be impediments to change and

progress; they can be the wind that carries this change.

Imagine if communities across the world, entrenched in history and tradition, saw conservation as a viable way to preserve those histories. Because of the Morgan’s new message, the history and tradition associated with whaling will be relevant for many more decades to come.

The Morgan sailing again does not mean our oceans are fixed. It does not mean our relationship with our oceans is fixed. The Morgan's voyage is not a victory lap, but it can be the starting pistol.

To see video and photos of the Morgan's voyages in Stellwagen, check out the links below:

From Whaling to Watching

For

more of Evan Turk's travel illustration, check out the link below:

Evan Turk Travel Illustration

5 comments:

What an incredible essay, Evan! Bravo. Made me teary eyed. The words and the images here billow like the sails in the wind, and I can feel the rocking of the waves. <3

Fantastic, Evan! Thanks so much for sharing your magical trip on the Morgan!

Evan,

This is beautiful. I love the way your reportage captures the people as well as the place, and your reflections on the importance of the voyage are inspiring.

So glad you were there to capture a magical day.

Susan Funk

I can feel the beauty and magic of the day, and the importance of it's meaning. Wonderful Evan.

Thank you all! I was so proud to be there.

Post a Comment